CLIMATE MOBILIZATION ACT & LOCAL LAW 97

PART 2: IMPACT ON BUILDING OWNERS

Tzvi Karoly & Jack Jenkins

A quick search will uncover plenty of articles discussing the Climate Mobilization Act (CMA) and Local Law 97 (LL97), but few that focus on what they really mean for building owners. In this article, we look at three ways in which the CMA and LL97 may impact the industry moving forward:

- Costs

- Lease Language

- Rental Income

If you missed part one: find it here.

How Much Will LL97 Cost?

As discussed in part one – the stated goal of LL97 is to incentivize improvements that will reduce the annual energy use emissions of buildings. It aims to do this by assigning penalties to buildings that make failing to stay below prescribed emissions limits more costly.

Starting in 2024, once a building exceeds its annual allowance, the penalty kicks in and makes using each additional unit of energy more expensive. Adding 7.74 cents per kWh of electricity; $1.46 per hundred cubic feet of natural gas; $14.40 per Mlb of Con Edison Steam; $2.74 per gallon of No.2 Fuel Oil; and $2.95 per gallon of No.4 Fuel Oil.

Taking the law at face value, owners can either pay more in penalties, or pay more in capital costs. In reality, it is not so simple, as: i) there are other ways to reduce LL97 penalty costs; ii) capital spending that reduces exposure to LL97 penalties will often also reduce energy costs and improve the building in other ways; and iii) lease language often fails to assign penalty costs in a way that will incentivize reductions. For now, let’s take the law at face value and look at the overall cost it could add to a building each year.

To do this it is useful to think of the projected penalties in relation to either anticipated utility costs, or rental income. The utility costs for a building depend on many factors. In NYC, utility costs ranging from $3-$6/RSF are common (note: this includes both base building utilities as well as direct tenant energy meters). In comparison, some of the most energy intensive buildings may be facing up to $1.50/RSF in annual LL97 penalties from 2030 (equivalent to a 25% to 50% increase in energy costs). This can amount to millions of dollars per year for the largest buildings.

For a Class A building charging $80/RSF in rent, LL97 penalty costs could equate to a meaningful percentage of rental revenues. Although B or C buildings are often less energy intensive, meaning penalties are likely not as severe, they may equate to a larger percentage of the lower $/RSF rental income of these buildings.

Fortunately, building owners who work toward improving energy performance will see savings in both utility costs and penalty reductions (as well as an improved Energy Efficiency Grade – see below). Incentives offered by various State and utility entities can also further enhance the payback. These will be discussed in more detail in a future article.

A Tale of Two Buildings

Two midcentury buildings, A and B, each expect to avoid LL97 penalties for 2024 through 2029. They both use district steam and maintain 100% occupancy. They each expect to pay $1.00/sf annually from 2030, based on their current energy use – unless they cut emissions by 45%.

Building A uses lease language to pass all penalties to tenants as additional rent, including the 50% of current emissions that are due to energy use in base building equipment. Investing in upgrades to reduce these penalties will not directly benefit ownership under this arrangement so no improvements are made.

Building B instead uses lease language to share the allowance 50/50 with its tenants and only requires that tenants pay the penalties if their own submetered electricity use exceeds their share of the allowance. Ownership also invests in upgrades that reduce base building steam and electricity use by 45%, eliminating ownership’s share of the penalty costs.

Neither owner pays any penalties, but which is better off long term? The cost of being a tenant in building A has increased by $1.00/RSF. Meanwhile the cost of being a tenant in Building B has decreased by $0.75/RSF, as although tenants are paying $0.50/RSF in LL97 penalties the upgrades mean they are also paying around $1.25/RSF less for base building energy use. As a result: tenants in building B are $1.75/RSF better off than those in building A.

Provided the annualized cost of the upgrades is less than $1.75/RSF, ownership of building B should be better off long term, despite the initial expense. Tenants in building B are also more likely to invest in reducing their own energy use – further improving the building’s performance and energy grade – and making it more attractive to future tenants. This is because they see the full benefit of any resulting reduction in penalties (rather than having this shared pro-rata by all tenants).

How Is LL97 Changing Lease Language?

LL97 levies penalties upon building owners based on whole building energy use. For commercial buildings this invariably includes energy use by tenants, either via direct tenant utility meters, or submeters. By default, the penalty costs fall on the building but the ability to reduce (or increase) those costs is determined by the actions of both the building, and the building’s tenants – i.e., there is a split incentive problem.

Lease language is needed if the building wishes to pass a portion of the penalties through to tenants. As ‘penalties’ it is our understanding that they can’t simply be included in expenses unless specified in the lease.

Unfortunately, we are too often seeing lease language pass the full cost along to tenants – reducing the owner’s immediate exposure by reversing the split incentive, rather than fixing it. Long term, this approach may harm a building’s rental income: when underinvestment (in LL97 improvements) results in carbon performance falling behind that of peers and makes it less attractive to tenants (who are being asked to foot a bill they have only limited control over).

A better approach is to eliminate the split incentive. Where buildings do this, they should see lower LL97 penalties (or avoid them altogether) and may ultimately maintain a higher net income than those that do not. By appropriately sharing the costs among the building and each of the tenants, lease language can be used to incentivize all parties to act to reduce LL97 penalties when it is cost effective for them to do so.

Will The CMA Affect Rental Income?

This is an open question. However, knowing that savvy tenants are already interested in limiting their exposure to future penalty costs, consider the following related questions. Which building is more attractive to prospective tenants? The building that invests nothing while passing all costs to tenants, or one that shares the penalty costs while investing in reducing base building emissions? Is there a chance that occupancy rates will fall if a building passes higher operating expenses to its tenants than its peer group does? Finally, will a building’s energy letter grade combine with LL97 concerns in a way that will impact rental income?

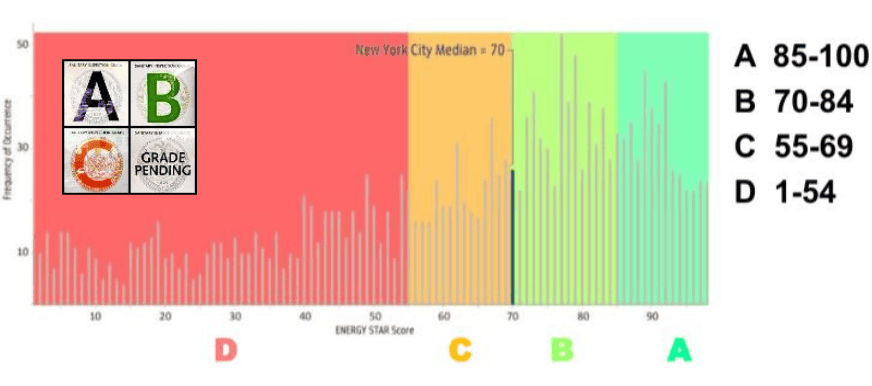

In the same way that tenants and their employees often seek out buildings with LEED certification, a good building energy grade, may become a proxy for lower costs and a key element in attracting and retaining good tenants. It behooves any forward-thinking landlord to work toward achieving as high a grade, and as carbon efficient an operation as possible.

LL97 penalty exposure and its equitable division between landlords and tenants is a new concept in the real estate community. RDE has found itself on both sides of the negotiating table at various times and has gained a deep understanding of how penalties can be equitably assigned, while using energy modeling and our own professional expertise to help owners determine their optimal approach to the law.

Tzvi Karoly, PE, CEA

Tzvi is engineering lead at RDE. He has spent more than a decade assisting commercial, institutional, and athletic facilities achieve their energy and sustainability goals.

Jack Jenkins, CEA, LEED AP BD+C

Jack is founder and director of RDE. He is a keen advocate for a greener economy and has been helping organizations to cut their energy and carbon costs for over 15 years. :: E-mail Jack at RDE

In part three, we will discuss how energy modeling can help owners and some building upgrades that can reduce carbon emissions.